어디에도 없는 행복의 순간, 그러나 느낄 수 있는 - 이 건 수 (미술비평·전시기획)

페이지 정보

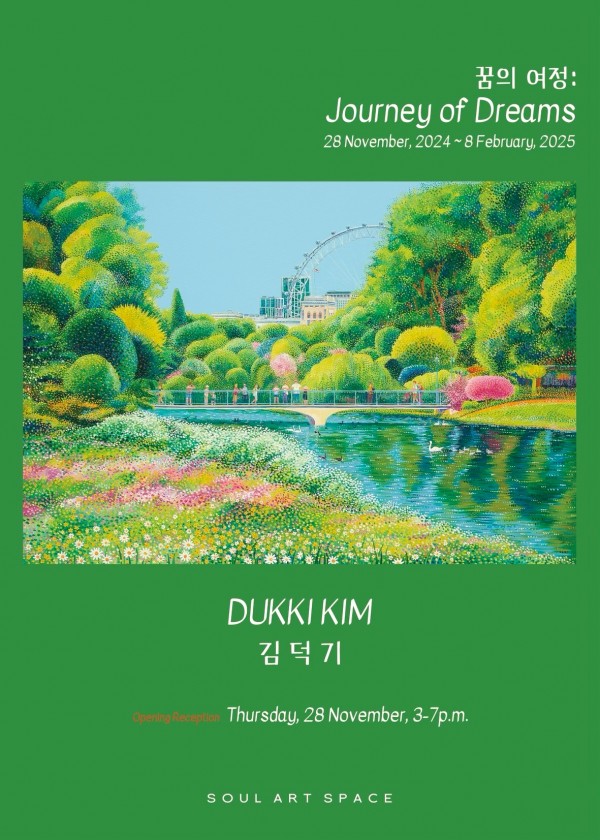

작성자 studio 작성일24-12-09 14:56 조회205회 댓글0건관련링크

본문

어디에도 없는 행복의 순간, 그러나 느낄 수 있는

이 건 수 (미술비평·전시기획)

‘아무리 원한다 해도 안되는 게 몇 가지 있지. 그 중에 하나 떠난 내 님 다시 돌아오는 것.

아쉬움뿐인 청춘으로 다시 돌아가는 것. 사랑하는 우리 엄마 다시 살아나는 것. 그때처럼 행복하는 것.’

―곽진언의 노래 <후회> 중에서

김덕기는 어느 누구의 화풍이나 어느 시대의 유파를 연상시키지 않으면서 자신 고유의 화면을 지속적으로 유지해왔다. 그것은 쉽고 만만한 그림처럼 보이지만 똑같이 모사하기 쉽지 않은 치밀하고 정밀한 그림이다. 복잡하고 화려한 화성학으로 짜여진 교향곡의 허황된 과장보다는 마치 모차르트의 명징한 한음 한음이 주는 진실성의 통렬한 찌름(punctum) 같은, 거짓을 허용하지 않는 순도 높은 명랑함의 광채가 가득하다. 모차르트가 라흐마니노프보다 더 어렵다.

이 완벽한 지복(至福)의 순간이 비현실적인 꿈과 동경의 픽션 속에서 피어난 신기루처럼 느껴지지만, 모두가 웃음 속에 파묻힌 이 천국의 한 컷의 바닥에 실은 그 높이에 비례하는 깊이의 슬픔과 고독이 채색되어 있음을 알게 된다면 이 행복의 높은 명도는 더욱 애틋한 아득함으로 다가오게 될 것이다.

한국화를 전공한 작가의 ‘현대판 도원경’ 속에서 동양화의 본질적인 개념과 본래적인 가치를 읽어내기란 어렵지 않다. 과거 동양화의 산수는 결국 기억과 인상의 이상적인 기록인 관념 산수가 대부분이다. 여기서 관념적이라는 것은 구체적이고 현실적인 세계-대상 그 자체의 모사가 아니라 산수라는 자연적 풍광이 품고 있는 세계의 진실을 이상적인 구조 속에서 은유적이고 상징적으로 배치시키는 것을 의미한다. 거대하고 숭고한 풍경 속에서 미미하게 그려진 나그네는 깊은 산중의 사찰이나 암자에 숨겨진 도(道)를 찾는 구도자이며, 그 천상의 도는 한줄기 폭포가 되어 이 하계(下界)에까지 흘러내리면서 만물의 궁극적 근원의 본성을 계시해준다.

김덕기의 파라다이스는 이런 전통 산수의 개념과 동떨어져 있지 않다. 완전한 현대판 산수가 되기 위해서 모든 형상들은 리얼한 디테일을 제거해버리고 도안화 되고 기호화 된다. 모든 부수적인 요소들을 벗어버리고 본질만 남은 그 형상들은 마치 고유명사화 된 언어처럼 그의 모든 화면들 속에서 재잘댄다. 그것은 하나의 사건의 기록으로만 남겨지지 않고 계속해서 이어지며 살아난다. 하나의 형상이 시간의 한계를 극복하고 초월하는 초현실성을 획득하는 순간이다.

역사화나 기록화, 특히 본격적인 종교화에서 쓰이는 몇가지 법칙이 있다. 정면성, 대칭성, 균제(symmetry), 수적인 통일은 화면에 기념비적인 항구성을 부여한다. 이런 방식이 고대적인 컴포지션의 전형이라고 한다면, 김덕기는 고대적인 문법 위에 더 나아가 서구 고전주의가 추구했던 완벽한 구도와 이상적 서사의 가상현실을 연출하고 있다. 소위 스튜디오 제작 방식이란 현장 그대로의 모습을 모사하는 것이 아니라 그림의 소재가 되는 모든 파편적 부분 요소들을 화면 속에 완벽한 기하학적 비율과 역학, 리듬으로 재배치함으로써 ‘만들어진 이상향’, ‘연출된 무대 위의 드라마’, ‘관념적인 미적 세계의 완성’을 성취하려는 것이었다.

전통적인 예술론의 근본적 원리인 “아름다운 자연의 모방”이란 말은 아름다운 자연을 모방(모사, copy)하는 것이 아니라, 자연을 아름답게―이상화하여― 모방(재현, representation)한다는 것을 의미한다. 어순을 바꿔 “자연의 아름다운 모방”이라고 표현하는 것이 더 정확하다 할 것이다. 작가는 가족이라는 모티프를 이상화된 완벽한 모방의 조건 속에서 영원히 변치 않을 이상향의 모습으로 구성하려 한다. 히에로니무스 보스의 <쾌락의 정원> 등과 같은 종교적인 삼면화나 제단화에서 보이는 ‘다양성의 통일’이나 ‘부분과 전체의 조화’가 작가의 주관적인 재구성을 통해 화면 속에 펼쳐진다. 자유로운 리듬감의 공간 활용과 색채―본질적으로 오방색과 무관하지 않은―의 현란함 속에서 느껴지는 단순하고 안정적인 톤과 구도의 통일성은 가벼운 삽화성의 일러스트레이션이길 거부하는 회화적 정통성을 획득하고 있다.

작가는 자신의 화면 구성이 지닌 장점이자 특성을 “동양적 시점(eastern perspective)”이라고 지적한다. 어찌 보면 삼원법과 같은 전통 동양화의 시점이라는 것이 가장 현대적인 퍼스펙티브일 수도 있겠다. 산점투시, 시점의 이동을 통한 탈(脫)원근법의 화면은 3차원에 머물러 있는 화면 위에 또 다른 차원을 부여하면서도, 동시에 회화가 지닌 평면적 본질을 부각시킬 수 있는 복합적인 시점이라 할 수 있다. 게다가 배산임수의 음양오행적 지리학은 화면 구성의 토대가 되면서 화면의 배경이 배경으로만 머무는 것이 아니라 스토리텔링의 주체가 되어 화면의 주조를 이끌어 간다.

모든 화면은 크게 보아 추상적 형태로 구획된 커다란 바닥면들이 우선적으로 채색되고 그 위에서 바닥 배색과 조화를 이루는 색점들과 필획들이 더해지는 색채의 층을 통해 화면의 깊이를 생성한다. 이것은 한지 위에 가로세로의 넓은 붓질로 마치 삼베와 같은 망 조직의 바닥을 먼저 만들어놓았던 그의 초기작을 다른 관점에서 상기시킨다. 가라앉은 시간성의 깊이 위에 정신적 여과의 과정을 거친 투명한 수묵 형상들이 어려있고 스며들어 있는 담담한 여백의 화면 구성이 그의 작품의 시작이자 본질이었다.

장욱진의 순진무구함의 먹그림이나 추사의 <세한도>에서 느껴지는 허심하고 싱거운 풍취의 담담함을 느끼게 해주는 그의 초기작들은 모든 감각적인 것을 제거하면서 가장 정신적인 것의 응결만을 간신히 남겨놓은 것 같은, 선묘의 연속과 여백의 공간이 서로 뒤섞이며 그래서 그림의 먹선이 서체의 본질을 드러내주고 있는, 탈물질화된 형상의 고요한 기록과 흔적에 그는 몰입했었다.

2006년부터는 수묵에서 채색으로, 종이에서 캔버스로 소재적 해석과 표현적 기법의 전환이 본격화 되는데 선과 면에서 점으로, 겹과 깊이의 수묵에서 폭과 확산의 채색으로의 전이가 이루어지게 된다. 동양적 퍼스펙티브를 통한 서양적 질료로의 운용 속에서 색면은 점차 색점으로 해체되는데 이때 서양의 후기인상주의나 광학주의가 추구한 색분해의 과정으로 김덕기의 ‘미점준(米點㕙)’을 이해해서는 안 될 것이다. 그의 색점은 색분해와 병치에 의한 점묘라기보다는 거꾸로 색면과 형상을 구성해가는 주요 인자이자 요소로서 당당하게 작용하게 된다.

하나의 색점은 전체의 색점들 속에서 점멸하며 흔들리고, 전체의 색점들은 하나하나의 색점으로 인해 생성하며 변화한다. 이런 발묵하고 파묵하는 것 같은 색채의 농담과 변주(variation)는 ‘동양화 같은 서양화’, ‘서양화 같은 동양화’의 또 다른 전형을 창출해냈다. 보편성의 회화, 우리시대 새로운 문인화의 모델이 성취된 것이다.

또한 파울 클레의 동심(童心)적 선묘를 연상시키며 다른 맥락에서 함께 진행되고 있는 ‘라인 드로잉’ 시리즈는 분필의 질감을 느끼게 하는 오일스틱의 드로잉 자체를 화면 뒤로 후퇴시키고, 그 드로잉이 구획한 색면 공간을 부각시키면서 선과 면의 역전과 반전으로 각인된 음화(陰畫)적 특성을 보여주고 있다.

작가는 시서화의 일치를 추구하며 ‘시중유화(詩中有畵) 화중유시(畵中有詩)’의 경지에 도달하고자 한다. 그래서 그의 가족우화 속에는 언제나 시가 흐르고 있고, 그가 그리는 유토피아적 풍경은 어디에도 존재하지 않는 꿈과 동경의 나라에 대한 찬가가 된다. 부모님을 잃은 10대의 시골 소년은 부모님의 부재로 인한 절대적 상실감과 절망감을 그림과 시로써 달랬을 것이다. 눈이 부시게 행복한 그림 속 가족들의 밝은 웃음들, 그 초현실적으로 찬란한 광채의 풍경이 이 선량한 화가가 침잠했던 아득한 깊이의 시간을 배경으로 하고 있다는 사실을 알게 될 때 우리는 이 그림을 결코 가볍게 대할 수 없게 될 것이다.

‘엄마 아빠, 당신들이 계신 곳의 정원이 이와 같지 않나요? 저는 이곳에서 이미 그곳을 바라봅니다. 저는 이미 이렇게 행복합니다.’

A moment of happiness found nowhere else, yet tangibly felt

Kenshu Li (Art Criticism and Exhibition Planning)

“No matter how much I wish, there are some things that just can’t happen. One of them is my departed love returning to me. Going back to my fleeting youth full of regrets. My beloved mother coming back to life. Being as happy as I was back then.” ―From Kwak JinEon’s song <Regret>

Dukki Kim has consistently maintained a unique style, unrelated to any particular art movement or era. His seemingly simple works are intricate and precise, challenging to replicate. Rather than the grandiosity of a symphony woven with complex, opulent harmonics, his paintings resonate with a high-spirited clarity akin to the piercing punctum found in each of Mozart’s crystalline notes—a brilliance that permits no falseness. Mozart, in fact, is more difficult than Rachmaninoff. This perfect moment of bliss may seem like an unreal mirage born of fictional dreams and aspirations, yet one may eventually discern, beneath this heavenly scene filled with smiles, a sadness and solitude proportionate to its height. Such depth and poignancy add a profound remoteness to the radiant brightness of this happiness, making it all the more tender and poignant longing.

In the "modern version of paradise" created by this artist trained in traditional Korean painting, one can readily discern the essential concepts and inherent values of oriental painting. Traditional Eastern landscape painting often recorded idealized impressions and memories, arranging nature's truth metaphorically and symbolically rather than realistically. In these scenes, the tiny traveler, seeking truth in a temple hidden deep in the mountains, reflects the cosmic flow of Dao(道) revealed through elements like a cascading waterfall. Kim's paradise aligns with this tradition, transforming all forms into simplified, symbolic designs, stripped of detail and reduced to their essence. These shapes, like unique symbols, come alive across his works, transcending time to achieve a surreal continuity that defies mere documentation.

Historical and religious paintings often follow rules like frontality, symmetry, and numerical unity, lending a monumental permanence to the composition. Building on this ancient framework, Dukki Kim incorporates Western classicism’s pursuit of perfect composition and idealized narrative. The so-called studio production method approach rearranges fragmented elements into precise geometric balance and rhythm, creating a "constructed utopia" and a "staged aesthetic world" of perfected ideals.

The fundamental principle of traditional art theory, "imitation of beautiful nature," does not mean copying nature but idealizing and representing it beautifully. A more accurate phrasing might be "beautiful imitation of nature." The artist seeks to depict the family motif as an eternal utopia, idealized within perfect imitation. Inspired by religious triptychs like Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights, the unity in diversity and harmony between parts and the whole are reimagined through the artist's subjective lens. The use of free rhythmic spaces and vibrant colors—rooted in the essence of Obangsaek(five Korean traditional colors)—combined with simplicity and compositional stability, asserts a painterly authenticity beyond mere illustration.

The artist points out the strength and uniqueness of his compositions as rooted in an "Eastern Perspective" In some ways, the traditional oriental painting’s viewpoint, such as three-perspective method, might be considered the most contemporary form of perspective. The shift perspective, or the manipulation of viewpoints to achieve a departure from conventional perspective, provides an additional dimension to the surface of a three-dimensional image. Simultaneously, it highlights the flat, two-dimensional essence of painting, creating a complex perspective. Furthermore, the geomantic principle of baesanimsu (mountains in the back, water in the front) based on yin-yang and the five elements serves as the foundation of the composition. Here, the background does not merely remain in the background but assumes a central role in storytelling, guiding the composition's main narrative.

Each composition begins with large, abstractly divided base surfaces, painted first, followed by layers of color dots and brushstrokes that harmonize with the base, creating depth. This approach echoes his early works, where broad strokes on hanji formed a fabric-like texture. The tranquil empty spaces, infused with transparent ink forms shaped by a process of mental refinement, reflect the essence of his art.

His early works evoke the simplicity and serene charm of Chang Ucchin's pure ink paintings or Chusa Kim Jeonghui’s Sehando(Winter Scene). Stripping away all sensory elements, they focus on the essence of spirit, where flowing ink lines and empty spaces intertwine, revealing the essence of calligraphy. These works reflect his immersion in recording dematerialized, tranquil forms.

Since 2006, Dukki Kim has shifted from ink to color and from paper to canvas, transitioning from lines and planes to dots, and from layered depth to expansive diffusion. His use of color dots, influenced by Eastern perspective and Western materials, should not be seen as a process of color decomposition like Post-Impressionism or Optical Art. Instead, the dots actively construct color fields and forms, serving as essential compositional elements.

Each color dot flickers and shifts within the whole, while the entire composition evolves through the interplay of individual dots. This variation in tone and layering, reminiscent of traditional ink techniques, creates a new paradigm of "Eastern-like Western painting" and "Western-like Eastern painting," establishing a universal form of painting, achieving a model for a modern muninhwa (literati painting) for our time.

The "Line Drawing" series, reminiscent of Paul Klee's childlike lines, uses oil sticks with a chalk-like texture. The drawings recede into the background, highlighting the color-field spaces they define, creating a reversal of line and plane with a distinct negative-image quality.

The artist seeks harmony between poetry, calligraphy, and painting, striving for the realm of "poetry in painting, painting in poetry." His family allegories flow with poetic essence, and his utopian landscapes become hymns to a land of dreams and longing that exists nowhere else. As a rural boy who lost his parents in his teens, he likely soothed his profound loss through poetry and painting. The radiant smiles of families in his blissful works and the surreal brilliance of his landscapes reflect a depth of sorrow and longing. Knowing this, we cannot view his art lightly.

"Mom and Dad, isn’t the garden where you are like this? From here, I already see it. I am already this happy."

이 건 수 (미술비평·전시기획)

‘아무리 원한다 해도 안되는 게 몇 가지 있지. 그 중에 하나 떠난 내 님 다시 돌아오는 것.

아쉬움뿐인 청춘으로 다시 돌아가는 것. 사랑하는 우리 엄마 다시 살아나는 것. 그때처럼 행복하는 것.’

―곽진언의 노래 <후회> 중에서

김덕기는 어느 누구의 화풍이나 어느 시대의 유파를 연상시키지 않으면서 자신 고유의 화면을 지속적으로 유지해왔다. 그것은 쉽고 만만한 그림처럼 보이지만 똑같이 모사하기 쉽지 않은 치밀하고 정밀한 그림이다. 복잡하고 화려한 화성학으로 짜여진 교향곡의 허황된 과장보다는 마치 모차르트의 명징한 한음 한음이 주는 진실성의 통렬한 찌름(punctum) 같은, 거짓을 허용하지 않는 순도 높은 명랑함의 광채가 가득하다. 모차르트가 라흐마니노프보다 더 어렵다.

이 완벽한 지복(至福)의 순간이 비현실적인 꿈과 동경의 픽션 속에서 피어난 신기루처럼 느껴지지만, 모두가 웃음 속에 파묻힌 이 천국의 한 컷의 바닥에 실은 그 높이에 비례하는 깊이의 슬픔과 고독이 채색되어 있음을 알게 된다면 이 행복의 높은 명도는 더욱 애틋한 아득함으로 다가오게 될 것이다.

한국화를 전공한 작가의 ‘현대판 도원경’ 속에서 동양화의 본질적인 개념과 본래적인 가치를 읽어내기란 어렵지 않다. 과거 동양화의 산수는 결국 기억과 인상의 이상적인 기록인 관념 산수가 대부분이다. 여기서 관념적이라는 것은 구체적이고 현실적인 세계-대상 그 자체의 모사가 아니라 산수라는 자연적 풍광이 품고 있는 세계의 진실을 이상적인 구조 속에서 은유적이고 상징적으로 배치시키는 것을 의미한다. 거대하고 숭고한 풍경 속에서 미미하게 그려진 나그네는 깊은 산중의 사찰이나 암자에 숨겨진 도(道)를 찾는 구도자이며, 그 천상의 도는 한줄기 폭포가 되어 이 하계(下界)에까지 흘러내리면서 만물의 궁극적 근원의 본성을 계시해준다.

김덕기의 파라다이스는 이런 전통 산수의 개념과 동떨어져 있지 않다. 완전한 현대판 산수가 되기 위해서 모든 형상들은 리얼한 디테일을 제거해버리고 도안화 되고 기호화 된다. 모든 부수적인 요소들을 벗어버리고 본질만 남은 그 형상들은 마치 고유명사화 된 언어처럼 그의 모든 화면들 속에서 재잘댄다. 그것은 하나의 사건의 기록으로만 남겨지지 않고 계속해서 이어지며 살아난다. 하나의 형상이 시간의 한계를 극복하고 초월하는 초현실성을 획득하는 순간이다.

역사화나 기록화, 특히 본격적인 종교화에서 쓰이는 몇가지 법칙이 있다. 정면성, 대칭성, 균제(symmetry), 수적인 통일은 화면에 기념비적인 항구성을 부여한다. 이런 방식이 고대적인 컴포지션의 전형이라고 한다면, 김덕기는 고대적인 문법 위에 더 나아가 서구 고전주의가 추구했던 완벽한 구도와 이상적 서사의 가상현실을 연출하고 있다. 소위 스튜디오 제작 방식이란 현장 그대로의 모습을 모사하는 것이 아니라 그림의 소재가 되는 모든 파편적 부분 요소들을 화면 속에 완벽한 기하학적 비율과 역학, 리듬으로 재배치함으로써 ‘만들어진 이상향’, ‘연출된 무대 위의 드라마’, ‘관념적인 미적 세계의 완성’을 성취하려는 것이었다.

전통적인 예술론의 근본적 원리인 “아름다운 자연의 모방”이란 말은 아름다운 자연을 모방(모사, copy)하는 것이 아니라, 자연을 아름답게―이상화하여― 모방(재현, representation)한다는 것을 의미한다. 어순을 바꿔 “자연의 아름다운 모방”이라고 표현하는 것이 더 정확하다 할 것이다. 작가는 가족이라는 모티프를 이상화된 완벽한 모방의 조건 속에서 영원히 변치 않을 이상향의 모습으로 구성하려 한다. 히에로니무스 보스의 <쾌락의 정원> 등과 같은 종교적인 삼면화나 제단화에서 보이는 ‘다양성의 통일’이나 ‘부분과 전체의 조화’가 작가의 주관적인 재구성을 통해 화면 속에 펼쳐진다. 자유로운 리듬감의 공간 활용과 색채―본질적으로 오방색과 무관하지 않은―의 현란함 속에서 느껴지는 단순하고 안정적인 톤과 구도의 통일성은 가벼운 삽화성의 일러스트레이션이길 거부하는 회화적 정통성을 획득하고 있다.

작가는 자신의 화면 구성이 지닌 장점이자 특성을 “동양적 시점(eastern perspective)”이라고 지적한다. 어찌 보면 삼원법과 같은 전통 동양화의 시점이라는 것이 가장 현대적인 퍼스펙티브일 수도 있겠다. 산점투시, 시점의 이동을 통한 탈(脫)원근법의 화면은 3차원에 머물러 있는 화면 위에 또 다른 차원을 부여하면서도, 동시에 회화가 지닌 평면적 본질을 부각시킬 수 있는 복합적인 시점이라 할 수 있다. 게다가 배산임수의 음양오행적 지리학은 화면 구성의 토대가 되면서 화면의 배경이 배경으로만 머무는 것이 아니라 스토리텔링의 주체가 되어 화면의 주조를 이끌어 간다.

모든 화면은 크게 보아 추상적 형태로 구획된 커다란 바닥면들이 우선적으로 채색되고 그 위에서 바닥 배색과 조화를 이루는 색점들과 필획들이 더해지는 색채의 층을 통해 화면의 깊이를 생성한다. 이것은 한지 위에 가로세로의 넓은 붓질로 마치 삼베와 같은 망 조직의 바닥을 먼저 만들어놓았던 그의 초기작을 다른 관점에서 상기시킨다. 가라앉은 시간성의 깊이 위에 정신적 여과의 과정을 거친 투명한 수묵 형상들이 어려있고 스며들어 있는 담담한 여백의 화면 구성이 그의 작품의 시작이자 본질이었다.

장욱진의 순진무구함의 먹그림이나 추사의 <세한도>에서 느껴지는 허심하고 싱거운 풍취의 담담함을 느끼게 해주는 그의 초기작들은 모든 감각적인 것을 제거하면서 가장 정신적인 것의 응결만을 간신히 남겨놓은 것 같은, 선묘의 연속과 여백의 공간이 서로 뒤섞이며 그래서 그림의 먹선이 서체의 본질을 드러내주고 있는, 탈물질화된 형상의 고요한 기록과 흔적에 그는 몰입했었다.

2006년부터는 수묵에서 채색으로, 종이에서 캔버스로 소재적 해석과 표현적 기법의 전환이 본격화 되는데 선과 면에서 점으로, 겹과 깊이의 수묵에서 폭과 확산의 채색으로의 전이가 이루어지게 된다. 동양적 퍼스펙티브를 통한 서양적 질료로의 운용 속에서 색면은 점차 색점으로 해체되는데 이때 서양의 후기인상주의나 광학주의가 추구한 색분해의 과정으로 김덕기의 ‘미점준(米點㕙)’을 이해해서는 안 될 것이다. 그의 색점은 색분해와 병치에 의한 점묘라기보다는 거꾸로 색면과 형상을 구성해가는 주요 인자이자 요소로서 당당하게 작용하게 된다.

하나의 색점은 전체의 색점들 속에서 점멸하며 흔들리고, 전체의 색점들은 하나하나의 색점으로 인해 생성하며 변화한다. 이런 발묵하고 파묵하는 것 같은 색채의 농담과 변주(variation)는 ‘동양화 같은 서양화’, ‘서양화 같은 동양화’의 또 다른 전형을 창출해냈다. 보편성의 회화, 우리시대 새로운 문인화의 모델이 성취된 것이다.

또한 파울 클레의 동심(童心)적 선묘를 연상시키며 다른 맥락에서 함께 진행되고 있는 ‘라인 드로잉’ 시리즈는 분필의 질감을 느끼게 하는 오일스틱의 드로잉 자체를 화면 뒤로 후퇴시키고, 그 드로잉이 구획한 색면 공간을 부각시키면서 선과 면의 역전과 반전으로 각인된 음화(陰畫)적 특성을 보여주고 있다.

작가는 시서화의 일치를 추구하며 ‘시중유화(詩中有畵) 화중유시(畵中有詩)’의 경지에 도달하고자 한다. 그래서 그의 가족우화 속에는 언제나 시가 흐르고 있고, 그가 그리는 유토피아적 풍경은 어디에도 존재하지 않는 꿈과 동경의 나라에 대한 찬가가 된다. 부모님을 잃은 10대의 시골 소년은 부모님의 부재로 인한 절대적 상실감과 절망감을 그림과 시로써 달랬을 것이다. 눈이 부시게 행복한 그림 속 가족들의 밝은 웃음들, 그 초현실적으로 찬란한 광채의 풍경이 이 선량한 화가가 침잠했던 아득한 깊이의 시간을 배경으로 하고 있다는 사실을 알게 될 때 우리는 이 그림을 결코 가볍게 대할 수 없게 될 것이다.

‘엄마 아빠, 당신들이 계신 곳의 정원이 이와 같지 않나요? 저는 이곳에서 이미 그곳을 바라봅니다. 저는 이미 이렇게 행복합니다.’

A moment of happiness found nowhere else, yet tangibly felt

Kenshu Li (Art Criticism and Exhibition Planning)

“No matter how much I wish, there are some things that just can’t happen. One of them is my departed love returning to me. Going back to my fleeting youth full of regrets. My beloved mother coming back to life. Being as happy as I was back then.” ―From Kwak JinEon’s song <Regret>

Dukki Kim has consistently maintained a unique style, unrelated to any particular art movement or era. His seemingly simple works are intricate and precise, challenging to replicate. Rather than the grandiosity of a symphony woven with complex, opulent harmonics, his paintings resonate with a high-spirited clarity akin to the piercing punctum found in each of Mozart’s crystalline notes—a brilliance that permits no falseness. Mozart, in fact, is more difficult than Rachmaninoff. This perfect moment of bliss may seem like an unreal mirage born of fictional dreams and aspirations, yet one may eventually discern, beneath this heavenly scene filled with smiles, a sadness and solitude proportionate to its height. Such depth and poignancy add a profound remoteness to the radiant brightness of this happiness, making it all the more tender and poignant longing.

In the "modern version of paradise" created by this artist trained in traditional Korean painting, one can readily discern the essential concepts and inherent values of oriental painting. Traditional Eastern landscape painting often recorded idealized impressions and memories, arranging nature's truth metaphorically and symbolically rather than realistically. In these scenes, the tiny traveler, seeking truth in a temple hidden deep in the mountains, reflects the cosmic flow of Dao(道) revealed through elements like a cascading waterfall. Kim's paradise aligns with this tradition, transforming all forms into simplified, symbolic designs, stripped of detail and reduced to their essence. These shapes, like unique symbols, come alive across his works, transcending time to achieve a surreal continuity that defies mere documentation.

Historical and religious paintings often follow rules like frontality, symmetry, and numerical unity, lending a monumental permanence to the composition. Building on this ancient framework, Dukki Kim incorporates Western classicism’s pursuit of perfect composition and idealized narrative. The so-called studio production method approach rearranges fragmented elements into precise geometric balance and rhythm, creating a "constructed utopia" and a "staged aesthetic world" of perfected ideals.

The fundamental principle of traditional art theory, "imitation of beautiful nature," does not mean copying nature but idealizing and representing it beautifully. A more accurate phrasing might be "beautiful imitation of nature." The artist seeks to depict the family motif as an eternal utopia, idealized within perfect imitation. Inspired by religious triptychs like Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights, the unity in diversity and harmony between parts and the whole are reimagined through the artist's subjective lens. The use of free rhythmic spaces and vibrant colors—rooted in the essence of Obangsaek(five Korean traditional colors)—combined with simplicity and compositional stability, asserts a painterly authenticity beyond mere illustration.

The artist points out the strength and uniqueness of his compositions as rooted in an "Eastern Perspective" In some ways, the traditional oriental painting’s viewpoint, such as three-perspective method, might be considered the most contemporary form of perspective. The shift perspective, or the manipulation of viewpoints to achieve a departure from conventional perspective, provides an additional dimension to the surface of a three-dimensional image. Simultaneously, it highlights the flat, two-dimensional essence of painting, creating a complex perspective. Furthermore, the geomantic principle of baesanimsu (mountains in the back, water in the front) based on yin-yang and the five elements serves as the foundation of the composition. Here, the background does not merely remain in the background but assumes a central role in storytelling, guiding the composition's main narrative.

Each composition begins with large, abstractly divided base surfaces, painted first, followed by layers of color dots and brushstrokes that harmonize with the base, creating depth. This approach echoes his early works, where broad strokes on hanji formed a fabric-like texture. The tranquil empty spaces, infused with transparent ink forms shaped by a process of mental refinement, reflect the essence of his art.

His early works evoke the simplicity and serene charm of Chang Ucchin's pure ink paintings or Chusa Kim Jeonghui’s Sehando(Winter Scene). Stripping away all sensory elements, they focus on the essence of spirit, where flowing ink lines and empty spaces intertwine, revealing the essence of calligraphy. These works reflect his immersion in recording dematerialized, tranquil forms.

Since 2006, Dukki Kim has shifted from ink to color and from paper to canvas, transitioning from lines and planes to dots, and from layered depth to expansive diffusion. His use of color dots, influenced by Eastern perspective and Western materials, should not be seen as a process of color decomposition like Post-Impressionism or Optical Art. Instead, the dots actively construct color fields and forms, serving as essential compositional elements.

Each color dot flickers and shifts within the whole, while the entire composition evolves through the interplay of individual dots. This variation in tone and layering, reminiscent of traditional ink techniques, creates a new paradigm of "Eastern-like Western painting" and "Western-like Eastern painting," establishing a universal form of painting, achieving a model for a modern muninhwa (literati painting) for our time.

The "Line Drawing" series, reminiscent of Paul Klee's childlike lines, uses oil sticks with a chalk-like texture. The drawings recede into the background, highlighting the color-field spaces they define, creating a reversal of line and plane with a distinct negative-image quality.

The artist seeks harmony between poetry, calligraphy, and painting, striving for the realm of "poetry in painting, painting in poetry." His family allegories flow with poetic essence, and his utopian landscapes become hymns to a land of dreams and longing that exists nowhere else. As a rural boy who lost his parents in his teens, he likely soothed his profound loss through poetry and painting. The radiant smiles of families in his blissful works and the surreal brilliance of his landscapes reflect a depth of sorrow and longing. Knowing this, we cannot view his art lightly.

"Mom and Dad, isn’t the garden where you are like this? From here, I already see it. I am already this happy."

댓글목록

등록된 댓글이 없습니다.